How We Heal

New Yorkers are finding new ways to heal their minds and bodies. Here's a look at the landscape of alternative medicine in the Big Apple.In the South Ozone Park neighborhood of Queens, a man enters a local reiki center, seeking spiritual treatment for an illness he’s been battling for decades. In Manhattan’s Chinatown, a woman visits an acupuncture clinic, looking for relief from back pain. And in Midtown, a few dozen blocks north, a young man stands inside a glitzy medical marijuana dispensary, hoping to buy a cannabis-based tincture that will alleviate his anxiety.

After finding more conventional methods of treatment — like those offered by hospitals and pharmaceutical companies — did little to help, New Yorkers are finding relief through alternative forms of healing.

Unhappy with the current medical system, more people are venturing outside the mainstream healthcare industry, discovering new ways to deal with life’s maladies — methods that often in reality have ancient roots. Some are seeking treatment for specific physical illnesses and diseases, such as chronic pain and cancer. Others are looking for relief from emotional suffering, such as past traumas and grief. And some simply want a more holistic approach to well-being than an annual doctor’s visit.

Explainer: What do we mean when we say "alternative medicine?"

“Complementary,” “alternative,” “integrative” — there are a number of terms used to describe treatments and therapies outside the realm of conventional medicine. For the purposes of this project, “alternative medicine,” “alternative health,” and “unconventional medicine” are used interchangeably to refer to treatments that fall within this category.

“Conventional medicine” is used to describe the prevailing system of medicine in the United States. It is a system through which “medical doctors and other health-care professionals (such as nurses, pharmacists and therapists) treat symptoms and diseases using drugs, radiation or surgery,” according to the National Cancer Institute. It is also commonly known as “Western medicine” or “allopathic medicine.”

“Complementary medicine” refers to treatments that are done in conjunction with conventional medicine. They include yoga, acupuncture and chiropractic. “Alternative medicine” is treatment used in place of conventional medicine. Included in this category are traditional faith healing systems.

“Integrative medicine” combines both conventional and nonconventional strategies for a more holistic approach to health.

It’s a movement that’s fueling the booming wellness industry, which grew to $4.2 trillion in 2017 from $3.7 trillion in 2015, according to a 2018 report by the Global Wellness Institute, a nonprofit devoted to health and wellness education. Within that industry, traditional and complementary medicines alone, including yoga, meditation and acupuncture, were worth $359.7 billion in 2017, an increase from $199 billion two years before.

But perhaps nowhere else is the alternative health trend more visible than in New York City, where you can choose from a vast array of services, from spiritual healers and acupuncturists to renowned teaching hospitals adding acupuncture to their rosters to practitioners on side streets to “bougie” weed dispensaries along Fifth Avenue. These businesses not only reflect the city’s rich cultural landscape but also demand for a different approach to health care. ‘How We Heal’ is a look at the burgeoning movement of alternative medicine in New York City today.

In Their Words: We went out and posed a question to New Yorkers: "What comes to mind when you think of 'alternative health'?”

Part I

The Rise of Alternative HealthFrom renowned teaching hospitals to unlicensed practitioners on side streets, alternative medicine has become big business, changed popular culture and led many Americans to try new modes of healing.

Acupuncture, once a fringe practice, is now being used in hospitals and covered by insurance providers. Doctors and nurses are working with experts on meditation, naturopathy and reiki to help patients with chronic illnesses while also providing primary care.

The science backing the effectiveness of many alternative methods, however, is limited and controversial. So how do New Yorkers decide whom they’re going to trust with their health? From purchasing a rose quartz crystal for remedying anxiety to ancestral healing practices that engage with spirituality, the face of alternative healing is ever-changing, and so is the science that studies it. Here is a look at the legitimacy of alternative medicine, what is simply taken on faith and how, for some believers, that may just be enough.

A Glossary of Alternative Healing

The array of alternative health forms out there is vast, but here we define a few of the more popular varieties.

Acupuncture

Acupuncture is an ancient Chinese form of healthcare that involves the insertion of thin needles through the skin at strategic points on the body. It is commonly used for pain but is being used more for overall wellness like stress management, migraines, menstrual cramps, back pain and respiratory disorders.

Crystal Healing

Crystal healing is a technique in which crystals and other stones are places on the body to draw out negative energy, cure ailments and protect against disease. Scientific evidence does not show that crystals and gems treat any ailments and most experts consider it a pseudoscience.

Aromatherapy

Aromatherapy is the use of essential oils from flowers, herbs and trees through direct and indirect inhalation as well as directly applied to the skin. The oils can be used for dermatological conditions such as eczema and lupus, and to improve energy, immunity, or digestion, and help alleviate insomnia and anxiety. Scents may have some physiological effects on the body, but evidence of healing properties are limited, and oils must be used carefully, be properly diluted, and can cause skin irritation.

Traditional Chinese Medicine

Traditional Chinese Medicine is an ancient practice that has expanded in China over thousands of years. It includes many practices including acupuncture, moxibustion, Chinese herbal medicine, dietary therapy and tai chi.

Marijuana

Marijuana has been used for a variety of conditions for at least 3,000 years, according to the National Institutes of Health. The FDA has not recognized or approved the plant as medicine but has approved two medications that contain cannabinoid chemicals in pill form, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Reiki

Reiki is a form of energy healing that dates back to the 1920s in Japan. The therapy involves a Reiki master lightly touching the body or hovering the hands over or alongside the body with intentions to speed healing, reduce pain, and promote deep relaxation.

Naturopathy

Naturopathy combines nature with the “rigors of modern science,” according to the Association of Accredited Naturopathic Medical Colleges. It can integrate dietary changes, stress reduction, herbs and supplements, exercise and psychotherapy.

More People Are Trying Out Alternative Medicine. Here’s Why.

By Nicolette Muro

A patient undergoes cupping therapy, a form of Chinese medicine involving the placement of suction cups on the skin to increase blood flow to the area.

A runner from Manhattan suffering from back pain tries an acupuncturist for the first time right before a big race.

A man in Chinatown struggling with inflammation tries turmeric to help his digestive system.

And a woman from a suburb north of New York City turns to a chiropractor to help with gastrointestinal problems that caused nausea and vomiting for most of her life.

“I get severe pain in my stomach,” said Camey Leandro, 51, a former dental assistant who had to retire after her gastrointestinal problems became severe. “Doctors had me on 15 different types of medications, and three were heavy narcotics,” she said.

“Finally, I had enough,” she said. “I detoxed and started all alternative care.”

These are just a few examples of people — exasperated with Western medicine and fed up with chronic pain — who are incorporating different forms of alternative medicine into their health-care routine.

Many people have begun using holistic approaches, and some hospitals are beginning to incorporate alternative medicine into their training. In an approach known as integrative health, doctors and nurses are working with experts on practices like meditation, acupuncture and reiki at some facilities to help patients with chronic illnesses.

Read More

A Holistic Approach

The Morrison Center in Murray Hill, Manhattan, for example, seems like a typical doctor’s office at first — but doctors aren’t prescribing pills or ordering surgeries.

Alternative healing clinics like the Morrison Center recommend all-natural healing methods instead of immediately prescribing drugs or issuing medical procedures.

Patients like Blanka Dmoszynska tried massage treatments and finally received a diagnosis after she says her rheumatologist failed to identify why she kept experiencing back and muscle pain.

“The pain is excruciating,” said Dmoszynska. “The guy that gives me massages says that I have tension, and he actually said that I have sciatica.”

And others are interested in alternative medicine because it is a holistic approach and they want to avoid potentially addictive painkillers.

“I would be more prone to take the alternative route first than to take the pharmaceutical route,” said Calvin Anthony. “Because people become dependent upon medication.”

Some people, however, are skeptical about trying alternative medicine because there are no guarantees that it will work. There’s also little science behind the use of the practices, according to studies.

Many people use chiropractic, for example, but the practice is not scientifically validated. It is founded on the incorrect principle that any health problem can be cured with spinal manipulation, according to studies.

Acupuncture and reiki, too, are controversial within the scientific community. Even though there are studies that say reiki works, many say it doesn’t.

“I use modern medicine,” said Nick Whittle. “That’s just what I’ve always done. I just don’t know that there’s the proof that alternative medicine works and that’s probably why I wouldn’t go down that path.”

Despite the skepticism some have, others are increasingly looking for alternative ways to heal. Jorge Sarabia, for instance, tried alternative medicine when an inflammation affected his entire body and he said doctors couldn’t prescribe anything that worked.

“What I did was go online and do my homework to find a real solution for my health problem,” said Sarabia. “Turmeric and lemon after I eat works wonders for me.”

And Katherine Flores, 48, the runner from Manhattan who tried an acupuncturist before her big race, wasn’t willing to turn to alternative healing until it was recommended by a friend and she was desperate to relieve her back pain.

“My close friend was seeing an acupuncturist at the time and was having amazing results,” Flores said. “My race was in a week, and I didn’t feel like it was going to work to go to the doctor. So, I just gave the acupuncturist a shot and it worked.”

In Their Words: What alternative treatments are New Yorkers using?

Why Americans Are Turning to Forms of Healing That Aren’t Backed by Science

By Shira Feder

“Faerie oracle cards” and gemstones laid out during a reiki session at Blue Star New York.

At New York City’s Rock Star Crystals, customers rummaged through some of the hundreds of crystals for sale, ranging in price from 5 cents to over $10,000.

The shop, which bills itself as a “metaphysical store specializing in crystal healing and gemstone healing,” sells everything from baby onyx chips to a 100-pound smoky quartz cluster.

One customer fiddled with black shungite stones, believed to protect from the electronic magnetic fields emitted by electronic devices, while another, hoping to relieve stress, hovered near the display of rose quartz stones.

“What do you have for good luck?” still another customer asked, before being led to purple amethyst crystals.

Like the patrons at Rock Star Crystals who believe the stones can assist them physically and spiritually, many people are looking for ways to heal beyond conventional forms of medicine. Some turn to reiki, a touch-based therapy focused on energy pathways or acupuncture, which uses needles to alleviate pain and to treat various conditions.

Healing Hands: “Some offices will market themselves as a cure for this and that, but I don’t believe in that line of promising. I’m not promising anything. All I know is I’m going to give you chiropractic to allow your body to work properly,” said Adam Lamb, a chiropractor at Lamb Chiropractic, a clinic on Madison Avenue.

Some medical experts say the belief in those healing methods and others are fueled by the placebo effect. Researcher Luana Colloca, editor of the 2013 book “Placebo and Pain,” defined the phenomenon as an improvement in health due, in part, to belief in the treatment itself.

Paul Dieppe, a health and well-being professor at the University of Exeter Medical School in England, said that effect shouldn’t be taken lightly.

“What people say about a lot of these alternative treatments is, ‘Oh, they’re just a placebo effect,’” he said. “We should harness that effect and use it alongside alternative or conventional therapy rather than being critical.”

Dieppe says the placebo effect is all about patient-practitioner relationships. If a patient feels that their pain will be believed and their voices will be heard, he reasons, they are more likely to assume there will be a good outcome and feel better.

Read More The Placebo Effect Camey Leandro, a former dental hygienist, swears by her chiropractor’s healing abilities. “I can’t function unless I visit him once a week,” said Leandro, 51, who first started visiting the chiropactor to deal with her neck pains and gastrointestinal problems. Beyond those patients and practitioners who believe in them, alternative forms of healing have gone more mainstream. Prestigious medical schools like Harvard and Berkeley offer courses in alternative health. Many of these procedures are now covered by insurance, and the IRS allows residents to claim some of these procedures as medical deductibles. The science backing the effectiveness of crystals, acupuncture and reiki, and still other forms of alternative methods, is limited and controversial. Chiropractic, for example, is not scientifically validated. It is founded on the incorrect principle that any health problem can be cured with spinal manipulation, according to studies, like this seminal one by scientist and Harvard professor T.J. Kaptchuk. And even though there are studies that say reiki really works, there are others that that say it doesn’t. Still, it seems some people who use alternative health don’t care if it’s scientifically validated — they just care that it works. A 2012 study on reiki found improved anxiety levels among hospital patients receiving reiki along with cancer treatment. But patients were also receiving the attention and time of a nurse. That might have initiated the placebo effect, which made them feel they were feeling better. A 2018 study from the Mayo Clinic concluded that alternative treatments such as massage therapy and acupuncture were an effective treatment for alleviating patient pain — and potentially a replacement for opioids. Alternative methods that help people must be accepted more positively, Dieppe said. “It doesn’t matter to me how they work,” he said. “The fact is that millions of people are not wrong. They do help a lot of people.”

This African altar at the Sakhu Healing Center is full of offerings to various deities, including the Earth and Ocean gods. The altar stems from ancient African traditions, such as Yoruba, Ifa and West African vodun.

This African altar at the Sakhu Healing Center is full of offerings to various deities, including the Earth and Ocean gods. The altar stems from ancient African traditions, such as Yoruba, Ifa and West African vodun.

When Alternative Becomes Complementary: Integrative Health in NYC Hospitals

By Annie Todd and Deirdre Bardolf

The Tia Clinic in the Flatiron District in Manhattan blends conventional health care with alternative healing methods such as naturopathy, meditation and acupuncture. (Photo by Kezi Ban/Blonde Artists, courtesy of Rockwell Group)

On the surface, the Morrison Center in Murray Hill in Manhattan looks like a typical doctor’s office. Nurses bustle around in blue scrubs, patients check in at the front desk and the phone rings off the hook.

But a closer look reveals signs of just how different the center is: A bonsai tree sits in the center of the waiting room, bamboo stalks are propped up in the corner, and soft lights, natural wood and stone furbish the center with a spa-like energy.

Doctors don’t prescribe pills or order surgery, either.

“The one other thing that we give is hope,” said Dr. Jeffrey Morrison, who opened the clinic in 2002.

Hospitals and clinics across New York City, like the Morrison Center and the newly opened Tia Clinic, are blending conventional health care with alternative methods to provide a more holistic approach to the ailments and pains plaguing many New Yorkers. At these facilities, doctors and nurses work with experts on meditation, acupuncture, naturopathy and reiki to help patients with chronic illnesses while also providing primary care. It’s known as integrative health.

"The one other thing we give is hope."

At four major hospitals in the city, medical students are also learning how to use alternative treatments in their practice. Dr. Robert Schiller, the chief medical officer at the Institute of Family Health at Mount Sinai, has been using integrative therapies for decades.

“This is one of the things I was attracted to from the outset, figuring how to bring a lot of these techniques in,” said Schiller, who is also vice chairman of Family Medicine and Community Health at the Icahn School of Medicine.

Homeopathic treatments, acupuncture, hypnotherapy and other mind and body work are some aspects of patient treatment, according to Mount Sinai’s website. A 2018 study from the Mayo Clinic found that integrative treatments like these are effective in reducing patient pain in the hospital.

At the Morrison Center, patients typically come in three times a month for the whole treatment.

“We love it when patients come back and say they’re thrilled with the first set of recommendations,” said Morrison.

Read More

But Morrison acknowledges that not all patients will respond to the first set of recommendations. Sometimes it takes a few different tries to figure out which treatment is best, especially if the patient suffers from a chronic issue.

“A patient with a chronic issue might be with me for a year, but I’ve also seen a patient who reminded me it’s been 10 years that we’ve been working together,” he said.

The waiting room at the Morrison Center, an integrative clinic in Midtown Manhattan, where patients will typically come in three times a month.

The waiting room at the Morrison Center, an integrative clinic in Midtown Manhattan, where patients will typically come in three times a month.

Integrative Health Education

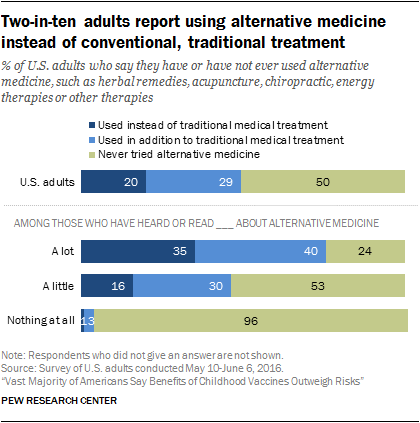

In general, people looking for new ways to heal are increasingly trying different forms of alternative medicine.

That expansion in alternative medicine users appears to have led to more interest in integrative health among students and doctors. The American Board of Physician Specialties, for example, offers a board certification in integrative medicine, which began in 2014.

Medical residents at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai also take a monthlong course in integrative health as part of the program.

“We’re developing the educational infrastructure and some of the accreditation process to determine who’s allowed to call themselves an integrated physician,” Schiller said.

Residents at the Icahn School with a particular interest in integrative medicine can take more courses through electives or additional training, Schiller said. The school recently started a fellowship program, which includes a certification in acupuncture for doctors interested in extra training.

“All of this is brand new,” said Schiller.

Deborah Valentin, a licensed acupuncturist and Chinese herbalist, runs a holistic healing center called Sage Wellness in Lower Manhattan.

When she was in her 20s, Valentin suffered from excruciating back pain. Her father, a doctor, advised her not to take any of the prescription pain medication. That’s when Valentin turned to acupuncture, and the experience was transformative.

Valentin said it “cured the physical pain and also restored a sense of inner peace.”

It also led her to pursue a master’s degree in health science and eastern medicine, studies that were not as widely accepted in the 1990s as they are now.

“I don’t try to convince anyone that it works,” Valentin said. “I rather them find out for themselves.”

Coverage and Costs

Costs vary widely depending on insurance coverage and doctor’s fees. At Mount Sinai’s Institute for Family Health, integrative services are covered by insurance including Medicaid and Medicare. The Institute also has a program where practitioners offer free homeopathy at six designated homeless sites across the city.

These sites include churches, single room occupancy buildings and transitional residences. Services provided range from getting key medication and treatments such as homeopathy to HIV testing, according to their website. At the two churches on the Upper West Side, they offer meals and showers during the week, and it coincides with the medical team’s schedule.

“What’s unique is the Institute of Family Health runs a network of federally qualified health centers so we’re a safety net provider,” Schiller said. “There are people who work in homeless shelters and free clinics. So we see people regardless of their ability to pay.”

On the other hand, the Tia Clinic, which opened in March in Manhattan’s Flatiron District, is membership-based, costing $15 a month or $150 for the year. They accept Aetna, Cigna, Empire Blue Cross Blue Shield, among other insurance providers. In the future, Tia hopes to expand to Medicaid coverage.

Without insurance, however, treatment costs are high. Members can expect to pay $123 for treatments for infections, such as UTIs, and other disorders, like endometriosis and polycystic ovary syndrome. Those treatments can cost upwards of $540 for a consultation and labs, according to its website. Non-members pay $425 out-of-pocket for individual naturopathy treatments and $400 for group wellness workshops.

Hospitals and clinics like Tia and the Morrison Center face a struggle to balance accessibility with coverage. Morrison said that at their clinic, it’s up to the doctor to choose what they want to charge. Most insurances don’t cover treatments.

The costs can give integrative health a bad reputation. “The people who charge outrageous amounts for integrative treatments are singled out as what’s wrong with the practice,” said Schiller.

But that doesn’t stop practitioners from trying to make it accessible.

Part II

From Free Reiki to Bougie Weed: The Business of Alternative MedicineNew York City is a mecca of alternative medicine. From Chinese herbalists in Manhattan to reiki masters in South Ozone Park, Queens, many have roots in the ethnic traditions brought by immigrants who continue to use the traditional healing practices of their home countries. There are Chinese herbalists in Queens, Caribbean-Latino botanicas in the Bronx and African-American spiritual healers in Brooklyn. And as public awareness of traditional and ethnic healing practices grows, entrepreneurs have taken note, repackaging once traditional remedies into luxury experiences for a more affluent clientele. New York is also home to spa-like naturopathy clinics and sleek marijuana dispensaries that look more like tech stores than spaces offering holistic treatments.

From the spiritual to the traditional, the $5 herbal concoctions in Flushing to $9 coffees laced with CBD oil, these practices reflect the city’s rich cultural landscape and the demand of residents willing to embrace a range of alternative treatments.

Global market value of traditional and complementary health, in billions of dollars

Number of "alternative medicine" businesses in New York City, according to Yelp

In Their Words: Alternative Medicine Providers Talk About Their Practice

In Ozone Park, the Healing Is Free

By Henna Choudhary

Blue Star New York, a holistic center in Ozone Park, Queens, offers a range of healing modalities, from reiki to qigong, at little to no cost.

Dressed in white from head to toe, Anupriya Lorick raises her arms toward the ceiling. In front of her, seven men and women sit peacefully in a semicircle of folding chairs. Light streams into the studio through a glass door, casting a single ray of sunshine on the mint-green walls decorated with photos of spiritual gurus, chakra charts and Hindu deities.

Angel figurines, scented candles and religious and cultural symbols from a gong to a bronze sculpture of Shiva, the Hindu god, are perched atop altars throughout the room. An embellished gold cloth laden with oracle cards and gemstones rests in the center.

“Allow the energy to guide you,” Lorick says as the men and women gently move their hands back and forth inches away from their bodies. They are practicing reiki, a touch-based healing technique said to help release stress and tension accumulated throughout daily routines.

Anupriya Lorick facilitates weekly reiki sessions at Blue Star.

The reiki class is one of several spiritual healing modalities offered for free, or with a voluntary donation to Blue Star Center of New York, a wellness center tucked away in residential South Ozone Park, Queens. The center — a branch of spiritual guru Sri Vasudeva’s international nonprofit, dedicated to holistic human development and community service — is among the wide range of facilities, from renowned teaching hospitals to spiritual healers on side streets, catering to New Yorkers who are looking for alternative forms of medicine and self-care.

“Even in a day that flows, usually there’s some form of stress somewhere,” said Yadira Carvajales, a graphic designer and bookkeeper who has been attending Blue Star’s classes for several years. “I’ve had headaches and felt sick and just walking into this space clears my auric field and it goes away. I don’t need medication,” she said.

Lorick founded the center after attending a 1997 workshop with Vasudeva. The center began with several of Vasudeva’s devotees gathering in living rooms to practice meditation. As a long-time resident of Ozone Park, Lorick noticed a lack of holistic treatment centers, pushing her to open one in her own neighborhood in October 2007.

Now, the center offers a selection of free wellness and spiritual sessions, including reiki, qigong — a martial art related to tai chi — interfaith fellowship, yoga and meditation retreats. Roughly 15 core members and locals drop-ins, mostly of Indo-Caribbean and Latin American descent, first became aware of the center by word of mouth.

Blue Star’s members say the practice has brought them relief in many ways.

Reiki is a healing technique, originating in Japan, based on the concept that practitioners can shift healing energy into another being or within themselves to activate natural healing processes of the body, restoring physical and emotional well-being.

“There’s a saying in reiki that it’s not that you find reiki, but reiki finds you,” said Anupriya Lorick, who is the vice president of Brookdale Hospital Medical Center’s human resources department by day and a certified reiki practitioner on evenings and weekends. “I think reiki offers people a different way of seeing their life and responding to their life, and as a result they naturally become healed,” she said.

Read More

Reiki has been adopted by hospitals and hospices to counter the side effects of debilitating treatments and medications. The Healing Touch Professional Association estimates that more than 30,000 nurses in U.S. hospitals use touch practices, including reiki, as a complementary therapy.

In a 2015 report, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services said that reiki hasn’t been clearly shown to produce beneficial results for health-related purposes and should not serve as a replacement to conventional care methods.

Blue Star’s members say the practice has brought them relief in many ways.

“The discipline of reiki helped me during my healing process, to understand what I was going through, help me quiet my mind, and concentrate on recovering from my illness,” said Mohan Sammy, 55, who has been attending Blue Star for 15 years, while being treated for congestive heart failure and recovering from a heart and kidney transplant. “During that time, I lost my power of speech twice. For years I couldn’t speak. The guidance of Sri Vasudeva and reiki helped me to be the person I am right now and learn to appreciate life,” he said.

Lorick, who leads weekly reiki sessions, received a master’s certification from the Reiki Arts Continuum and International House of Reiki and studied it in Japan and China. “I believe a lot of people need it and access is important. That means being reasonable, but fair with what you charge people,” said Lorick.

Lorick doesn’t charge for classes and instructs attendees to tap into their own healing energy force so they can apply reiki in stressful situations in their day-to-day lives.

“I came to understand that it’s something that’s already inside of me. This energy is already inside of me,” said Vidawattie Barsattee, 54, who has been a member of Blue Star since the day it was founded.

“Why not use what we already have to take care of ourselves, rather than looking elsewhere?” Barsattee said. “I have found that reiki has helped me mentally, emotionally, and physically and even long distance when I try to connect to someone that is going through a hard time, I’m able to extend that healing energy to them to help calm their mind.”

How One Controversial Cannabis Company Is Cashing In on Marijuana

By Chase Brush

MedMen, a high-end dispensary along Fifth Avenue, is one of the fastest-growing medical marijuana startups in the industry.

On Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue, in one of the top shopping districts in the world, passersby stop to study one storefront in particular. Sandwiched between a GNC vitamin shop and a Middle Eastern bakery, its glass and stone facade sets it apart.

Inside, rows of display counters showcase translucent gel capsules, small bottles of liquid and pen-like devices. Tablets atop the counters allow customers to explore details about each product, including cost and intended use. Sales associates in bright red T-shirts and hoodies stand nearby, ready to provide assistance.

To some visitors, the slick interior and hyperattentive employees recall the energy of an Apple store or cosmetics counter. But this is not your typical Fifth Avenue boutique. It’s MedMen, a cannabis retail company trying to bring marijuana into the mainstream.

“We really want to normalize and destigmatize cannabis,” said David Velazquez, a MedMen sales associate. “That’s what this place is all about.” He points to a large poster on the wall, which features an elderly woman above text that reads “Grandmother Stoner,” though the word “stoner” is crossed out.

Luxury Weed: At MedMen, rows of display counters showcase translucent gel capsules, small bottles of liquid and pen-like devices. All contain THC, the psychoactive component of cannabis.

As the business of alternative healing booms, it’s probably no surprise that the industry has come to cater to both the budget client and the affluent customer. On one end, small businesses and community providers offer their services and products to budget-conscious buyers seeking relief from everyday ailments. In New York, residents have bountiful access to a wealth of affordable alternative health sources, from botanicas to health clinics.

On the other end of the spectrum, larger companies have taken advantage of the global trend toward personal wellness and tapped into a luxury market for alternative healing products and practices. The health and wellness juggernaut Goop, owned by Gwyneth Paltrow, is a prime example: It has built its business on endorsing and offering advice on nontraditional medicines and practices, from reiki to yoni eggs. In New York, residents can also pay premium prices for a higher-end form of alternative healing.

Projected value of North American marijuana market in 2025, in billions

Tons of weed consumed by New Yorkers in 2018

MedMen —which recently partnered with Goop on a series of events and collaborations — fits in the latter category. As a publicly traded company in the U.S. and Canada now valued at over a billion dollars, it’s emerged as one of the largest players in the cannabis industry, with 19 manufacturing and retail spaces across five states, including New York, where it holds one of 10 licenses to operate medical marijuana dispensaries. Its mission, according to the founders, is to change public perception of the drug, transforming it from taboo to trendy.

To that end, the California-based company launched a high-profile advertising campaign last year, spending $4 million to put up billboards in tony Los Angeles neighborhoods and to hire filmmaker Spike Jonze to direct a commercial titled “The New Normal.”

This branding is on display in the company’s Fifth Avenue flagship location, which opened in April 2018. The store offers a sleek and stripped-down shopping experience, allowing customers to examine displays of tinctures and lotions at their leisure. The products are grouped into several different categories and are color-coded by strain, including green for “Wellness,” yellow for “Awakea” and purple for “Calm.” Pricing, even for medical marijuana, can be steep: a “LuxLyte” vape pen containing 190 milligrams of THC sells for $86, while a dropper containing 140 milligrams goes for $53.

Velazquez, the sales associate at MedMen, said dozens of people walk into the shop each day just to take a look around. For some prospective customer, shopping for weed in such a stylish atmosphere can feel surreal.

“I don’t know, man,” said Jake Robles, 22, a Bronx resident who visited MedMen on a recent Tuesday. “It just feels over the top.”

Robles does not have a medical marijuana card, which requires a doctor’s authorization to obtain, so he could not purchase products at Medmen. But he’s among a growing population of people who have turned to marijuana as a form of alternative healing. Once written off as little more than an illicit substance, cannabis is now heralded by recreational users and medical experts alike for its potential to relieve chronic pain, treat disorders like PTSD and help reduce the side-effects of cancer treatments.

In the U.S., approximately 44 percent of adults reported using marijuana, according to a 2017 poll by Yahoo News and Marist. Thirty-three states now have medical marijuana programs, while 10 have legalized it entirely. Together, the changes have given birth to a booming retail market: North America’s legal cannabis industry was worth an estimated $8.3 billion in 2017, according to New Frontier Data, a leading cannabis market research and data analysis firm, and it’s projected to reach almost $25 billion by 2025.

Still, marijuana’s growing popularity has also raised questions about how to regulate a drug that, in many areas of the country, is still illegal to carry and consume. In New York, cannabis can be obtained through the state’s medical program, which has grown in recent years to cover a wide variety of conditions, from HIV and AIDS to chronic pain. But a push to legalize recreational cannabis has yet to come to fruition, with lawmakers dropping the proposal from the state budget in March amid concerns over how the change would affect minority residents and people already arrested or incarcerated in connection with marijuana offenses.

On top of that, many officials are leery about opening up New York’s market to the kind of corporatization that has characterized the industry in other parts of the country.

“Legalization can follow two routes. In one, corporate cannabis rushes in and seizes a big, new market driven by a single motive: greed,” Mayor Bill de Blasio wrote in a 71-page report produced by the administration’s Task Force on Cannabis Legalization last year. “In another, New Yorkers build their own cannabis industry, led by small businesses and organized to benefit our whole diverse community.”

Some say MedMen already represents the corporate path. Last year, the company announced it would seek to acquire Pharmacann, another major player in the industry and one of New York’s nine other medical marijuana dispensaries, drawing scrutiny from state regulators who fear it might violate state law. MedMen has also been plagued by a series of financial and legal troubles, including a $20 million lawsuit by an early investor group, which charges that senior execs enriched themselves at the expense of shareholders.

Additionally, a class-action lawsuit was filed by a group of employees in California in December, in which they alleged major labor rights violations.

The issues have led some marijuana advocacy organizations to cut ties with the company: in February, the New York Medical Cannabis Industry Association asked MedMen to resign from its membership over allegations that the company’s CEO, Adam Bierman, used racially charged language to refer to a Los Angeles city councilman.

Still, New Yorkers seeking treatment are visiting the store. Robles, who said he’s suffered from anxiety for most of his life, was seeking more information about applying for a medical marijuana card. Figuring out how the state’s medical marijuana system works on his own has been difficult, he said.

“A lot of New Yorkers don’t have the access to get that medical marijuana card or even to get information about it,” he said. “So it’s hard for everyday people who are working 9 to 5, and who have these problems, to get treatment.”

Credits

Reporters

Editors

Annie Todd (Head of Research)

Deirdre Bardolf (Copy Editor)

Henna Choudhary (Social Media)

Nicolette Muro (Social Media)

Visual Producers

Web Producers

Project Manager

Faculty Advisers

Michelle Higgins

Wil Cruz

Christine McKenna

Katie Zavadski

Part I: The Rise Of Alternative Health

Part I: The Rise Of Alternative Health

Part II: From Free Reiki To Bougie Weed: The Business Of Alternative Medicine

Part II: From Free Reiki To Bougie Weed: The Business Of Alternative Medicine